We ship worldwide. Contact for custom quote!

- Home

-

Portfolio

- About Us

- Testimonials

- Blog

- Contact

We ship worldwide. Contact for custom quote!

April 20, 2020

Perhaps no other decorative object has proved so popular and enduring through the centuries and across diverse countries than the chandelier (see the glossary at the end of this article for a definition). Its history spans more than eight hundred years and as time progressed designs became ever more elaborate, reflecting the growing wealth and power of the highest echelons of society, as well as progress in terms of technological development and workmanship. Since its inception, the chandelier has been closely associated with royalty and the aristocracy which perpetuated its status as a symbol of wealth, luxury and grandeur. Mapping the evolution of the chandelier therefore involves tracing the history of the monarchs, principally between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, the time which saw the emergence of the most recognisable and timeless designs.

This article will focus on the three most prominent European chandelier styles to emerge, which include the French Rock Crystal, English glass and Venetian chandeliers. Whilst each of these had separate origins and followed distinct trajectories, it is important to note that fluidity across both time and space is a defining feature of the chandelier’s stylistic and technological evolution (Mccaffety, 2006). The high costs involved in manufacturing combined with the discerning tastes of its patrons, meant that the chandelier reflected rapidly changes in fashion and technology. In spite of some protectionist efforts, decorative styles circulated widely amongst designers, manufacturers and the ruling elite. Whilst such fluidity can make it challenging to track trends and attribute chandeliers, on the flip side it has contributed to creating a climate of innovation and a plethora of diversity and choice for consumers.

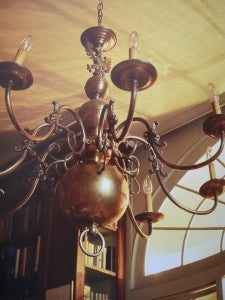

The first notable chandelier style to emerge and which was to have a lasting impact was the Dutch brass chandelier. Prior to this, chandeliers had been made of wood or iron, such as the Moorish iron farol from the eight century or the simple yet elegant iron corona which was widespread during the Middle Ages. These were all but superseded by the arrival of the Dutch-style chandelier by the fifteenth century. The defining feature of this chandelier is the central ball stem comprised of a large brass sphere, or series of ascending spheres, which support upward-curving arms. The Flemish town of Dinant, in what is now Belgium, became renowned for its fine brass wear, known as dinanderie. Brass was particularly suited to this design owing to its smooth surfaces which made it especially reflective of candlelight. Flemish chandeliers often incorporated Gothic symbolism, religious figures and stylised floral decoration. Particularly popular was the inclusion of a double-headed eagle emblem atop the chandelier, as in the illustration below (Smith, 1994).

Flemish chandeliers gained exposure and recognition through the church interiors of the Dutch Old Masters. Jan Van Eyck painted the earliest known image of a chandelier in 1434. This style of chandelier was also featured in many of the paintings by Gerrit Dou, who was a pupil of Rembrandt, such as in The Dropsical Woman created in 1663. Metal workers from Dinant dispersed across Europe which helped popularise the Flemish style far and wide. Dutch brass chandeliers became fashionable in France during the reign of Louis XIII (1610-43). But the style proved particularly enduring in England, which imported more Dutch brass wear than any other country, and where manufacturers were to emulate the basic design for centuries to come.

France is unique in Europe in that it did not start producing high quality glass until the late eighteenth century. Glass was generally not well-regarded when compared to materials such as porcelain, silver or ormolu. Instead, chandelier production was part of the metal working tradition and glass was substituted for rock crystal, a transparent form of quartz. This led to the development of the Rock Crystal chandelier. Whilst this style is most strongly associated with France, and with the palace of Versailles in particular, it spread quickly amongst Europe’s most luxurious residences and came to symbolise the epitome of wealth and grandeur.

This style of chandelier consists of a metal frame decorated with rock crystal pendants, drops and rosettes. They were made by metal workers who imported the crystal drops from various places throughout Europe, particularly Bohemia (today the Czech Republic). This widespread trade in drops can make it hard to date and pinpoint the exact origin of rock crystal chandeliers. The earliest drops were “hand cut on rather slow wheels” which meant they had a rather narrow angle of faceting (Smith, 1994). However, in time the process was mechanised using steam power in large factories which enabled deeper cutting. From around 1880 drops were polished with fluoric acid which significantly cheapened and quickened the process of finishing. Quartz is helix-shaped, resembling the diamond in its molecular structure and its natural crystallisation makes it more reflective than even the highest quality lead glass crystals (Mccaffety, 2006). As will be discussed, manufacturers later found a more affordable way to decorate chandeliers using glass, however quartz continued to be used to produce a few special fixtures.

The first chandeliers with rock crystals emerged in the seventeenth century. These were made in the Baroque style which spread across Europe from its birthplace in Florence following the Renaissance. Connections between rulers in Italy and France abounded during this time, and the arts and fashions of the Italian renaissance exerted a great influence over the French monarchs. Louis XIV (1643-1715), in particular, utilised architecture and the visual arts as a means to exert power and reflect his glory, a vision which resulted in the development of French Baroque, also known as le style Louis Quartoze. A typical chandelier from this period comprised an open or “birdcage” frame made of gilded bronze, either in a vase shape or in lyre shapes with bouquet tops, and decorated with shining cut rock crystals. The French Baroque chandelier is epitomised at Versailles. The Hall of Mirrors in the palace contains many Louis XIV crystal lustre.

By the end of the century two main types of French rock crystal chandeliers had emerged: the lustre à tige découverte in the style of Louis XIV; and the lustre à lace (also known as the Maria-Antoinetta, after the princess of Naples and Sicily) which was even more ornate, with the frame being completely covered in crystal beads and hung with pendants (Mccaffety, 2006). The sheer lavishness of these chandeliers set the standard for royal grandeur across Europe. For example, in 1667 Charles II of England proudly noted that he owned a rock crystal chandelier made in the Louis XIV style. France set and unified the fashions across Europe during this period and French Baroque would continue to influence designers, being revived on multiple occasions in the coming centuries.

Around 1725, the Rococo or “late Baroque” movement began to develop in France as a reaction against the perceived extravagant excess of the Baroque style. The Rococo style gained popularity during the reign of Louis XV. Typical chandeliers of this period were made of bronze and contained detailed designs featuring soft curves, irregular swirls and leaf-like motifs. They had sprouted flower candle cup nozzles and were often adorned with cupids, grotesques and garlands. The French designer Juste Aurèle Meissonier, who was appointed as a master goldsmith and designer by Louis XV, played an important role in popularising the Rococo style, particularly with his engravings featuring asymmetrical foliate motifs.

Following the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror and the Directory period (1794-1799), the French First Empire (1804-1815) led by Napoleon I was established. Up until this point, Louis XIV’s championing of Baroque had prevailed and set the fashions across Europe, but the fall of the house of Bourbon was to bring about significant changes in design. This reflected the shifting culture of the time characterised by growing disillusionment with the old ruling elite and increasing interest in the concept of democracy. The frivolity and decadence of Baroque and Rococo began to be eclipsed by the much more restrained neoclassical style.

Chandeliers made in this style drew heavily on the aesthetic of ancient Greece and Rome, incorporating clean lines, classical proportions and mythological creatures. Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign of 1798 resulted in an influx of looted artefacts which provided a wealth of ancient design inspiration in France. Jean-Charles Delafosse did much to popularise neoclassical motifs, such as a flame which was often featured at the centre of lamp style chandeliers. The anthemion motif, along with symbols of victory and references to the revolution, such as arrows, were also common additions to neoclassical chandeliers. The fleur-de lis, an ancient symbol long used to signify royalty, had topped many seventeenth century chandeliers, but was inverted by Napoleon and replaced with the Napoleonic bee to symbolise the overthrow of the Bourbon kings (Mccaffety, 2006).

The fashion for neoclassical design was felt all across Europe during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In England, James and Robert Adam were pre-eminent designers working in this style. They were strongly influenced by a trip to the archaeological sites at Pompeii and became dedicated proponents of neoclassicism alongside other designers of the time, most notably Thomas Chippendale, George Hepplewhite and Thomas Sheraton. Robert Adam (1728-1792) created a particularly influential neoclassical design, known as the Adam style, which went on to inspire later crystal chandeliers. It was long and slender, incorporating a Greek urn shape, an upper tier of arms bearing crystal spikes or spires, along with canopies, swags, pear-shaped dressings and elaborate drip pans (Mccaffety, 2006).

Following the French First Empire, the Louis Philippe style emerged (1830-1848) which was a late expression of neoclassicism, typified by heavier and bolder forms, but still drawing inspiration from the decorative elements of the First Empire style. Medieval themes and references to Greek mythology, including depictions of the griffin and chimera, also characterised chandelier design during this period (Mccaffety, 2006).

The Second Empire, presided over by Napoleon III (1850-70), was another period which borrowed significantly from earlier styles, particularly those associated with Louis XIV, XV and XVI. This is exemplified by Eugenie de Montijo, the Empress of Napoleon III, who was fascinated by Marie-Antoinette and the pre-revolutionary lifestyle in general, and sought to revive the fashions of these earlier periods. It was also during the nineteenth century that France began producing high quality glass chandeliers. In particular, the glass manufacturer Baccarat started making chandeliers out of lead glass in the 1820s, and has since become perhaps the most famous and successful producers of fine crystal in the world. Baccarat chandeliers are characterised by their clean lines and dense hanging prisms. Excellent examples can be seen in the Musée Baccarat in Paris.

A separate strand can be traced in the evolution of chandelier design, which took off following advancements in glass technology and resulted in the development of “all-glass” chandeliers, as opposed to metal frames decorated with rock crystals. These were made in England from the 1720s onwards after the discovery of lead or “double-flint” glass, but soon spread to glasshouses across Europe. Glass is not technically crystal, as its production process involves no crystallisation. However, it was designated as such, and as softer, more transparent and refractive types were developed it eventually came to replace the use of rock crystal in chandelier trimmings (Mccaffety, 2006).

England has a distinctive history in terms of chandelier production. This is partly due to the fact that the use of wood in the manufacture of glass was outlawed in 1615 meaning that there were no forest glasshouses unlike in other European countries where these were the predominant sites of glass production. Instead, glasshouses had to be built near to water in port cities such as Bristol so that the raw materials and finished glass could be easily transported. The resultant factory environment encouraged the development of rigorous apprenticeship schemes which fostered particularly high standards of workmanship (Smith, 1994).

In 1676, “flint glass” was created and patented by glass merchant George Ravenscroft. This contained a high percentage of lead oxide which improved the clarity of the glass and made it easier to cut, resulting in better refractive surfaces and prisms which created a glistening rainbow effect (Mccaffety, 2006). As a result of this innovation, England began producing the highest quality glass chandeliers of the time. “English” style chandeliers followed the designs of the brass ball-stem made famous by the Dutch Old Masters. The metal components, typically made of gilt or silvered, were limited to the main shaft, receiver bowl and receiver plate. Glass arms were fixed onto the receiver plates, twisted downwards at the base and then upwards with a holder and drip-pan for the candles being attached at the far end. As the eighteenth century progressed, more cuts were added to the glass to create deeper facets and more elaborate sparkle. In 1742 fused silver plating was created and placed inside the glass stem to act as a mirror, creating an illusion of solid glass (Mccaffety, 2006).

Examples of glass chandeliers dating from the early Georgian period can be found in the Assembly Rooms in York and also in the chapel of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. The stand-out examples of the Georgian-era crystal chandelier, however, are those hanging in the Assembly Rooms in Bath. These were made by William Parker, a glass manufacturer who was favoured by the English elite, including the Prince of Wales and Duke of Devonshire. In 1771 he was commissioned along with Jonathan Collet to design chandeliers for the Tea Room and Ball Room in Bath’s Assembly Rooms. Collet was charged with the more substantial project, however not long after the unveiling he became discredited after his chandeliers dropped three of their arms, were deemed unsafe and dismantled. Parker was subsequently hired to make replacements. The pieces he produced were highly praised and signalled several important advancements in chandelier design. Most significantly, he replaced the ball stem with vase-shaped stem pieces. This represented the first use of neoclassical elements, resulting in a more slender and elegant appearance, which ignited a fashion that was to prevail up until the Regency period.

The size of chandeliers increased considerably during this period. One particular chandelier fashioned by Parker for Carlton House, the London residence of the Prince of Wales, was fifteen feet tall. Significantly, Parker discovered that tapering the arms of large chandeliers was advantageous in terms of reducing the leverage of the sockets (Smith, 1994). Another important point about Parker’s chandeliers is that they were the first to include a reference to their maker. Name stamps became increasingly common from this point on, which reflected the growing importance of certain designers and manufacturers at the time and which now makes it easier to identify and attribute chandeliers.

An interesting development in the story of English chandeliers occurred in the late eighteenth century following the introduction of the Glass Excise Act in 1765 which levied a tax on all English glasshouses. This had a lasting impact on the industry as it encouraged many glassmakers to relocate to Ireland which was exempt from the tax. As a result, Ireland became a major centre for glass production in Great Britain. In particular, the Waterford Glass House, established by George and William Penrose in 1783, rose to prominence. This led to the development of the “Waterford Chandelier” which deviated from the earlier brass ball stem design. The producers of these chandeliers did not manufacture the glass they used. Instead, they either bought blanks or ready-cut drops from glassmakers. As the Waterford style developed, canopies were introduced providing extra scope for drops and pendants. Drops were also suspended from drip pans and chains and festoons were gradually added (Smith, 1994). There is a significant collection of Waterford chandeliers in the State apartments at Dublin Castle.

The Glass Excise Act tax also had important implications for the evolution of chandelier design in England. In fact, it inadvertently resulted in perhaps the most impressive and popular style ever to be created. This was the “English Regency” style, also known as the tent-and-bag chandelier. In an attempt to cut costs, manufacturers veered away from glass-arm chandeliers made from expensive crystal components. Instead, they used crystal drops cut from broken pieces of glass which they strung together in multiple swags and hung from the top of the chandelier to form a “tent” shape. Additional chains of drops were suspended from the bottom of the frame to create a “bag”. Hundreds of these drops were used across the entire length of the chandelier, and they were packed together so densely that the central stem and a good part of the metal frame were completely obscured. As there were no longer any glass arms, the candles were fixed into ormolu holders attached to the frame. This style emerged in England around 1790 and spread quickly across Europe. It gained particular appeal in France, so much so that it began to be referred to both as English Regency and French First Empire. The basic design also spawned thousands of variations in the years to follow. For example, around 1810, long slender icicle drops came to replace the pear-shaped drops of earlier versions. These would commonly be laid out in concentric circles, filling the entire base of the chandelier to create a waterfall effect.

The most distinguished English glassmaker of the early nineteenth century was William Perry, who followed in the footsteps of Parker, taking on the royal appointment as glass manufacturer to the Prince Regent, the future George IV. The Prince Regent was a chandelier enthusiast and commissioned Perry to produce several for Carlton House. This included a fifty-six light chandelier completed in 1808 which was fourteen feet high and considered to be one of the finest in Europe (link to image 13). Perry also produced nine “inverted parasol” chandeliers for the Music Room in Brighton’s Royal Pavilion (link to image 14). The typical style developed by Perry consisted of tall, narrow stem pieces, large top canopies adorned with swags and pear-shaped pendants, twisted rope glass arms and heart-shaped bottom finials. Perry partnered with Parker’s son to form Perry & Co in 1833. The influential company exported chandeliers worldwide, as far afield as China, until its dominance was superseded by F&C Osler later in the century.

The repeal of the Glass Excise Act in 1835 enabled English glassmakers to prosper. Chandeliers became an increasingly important aspect of the glass trade during this century, with numerous firms involved in their production. These were located principally in London but also in Liverpool, the country’s second largest port. John and James Davenport, Henry Greene and Hancock & Rixon were amongst the most prominent manufacturers, along with F&C Osler which dominated in the late nineteenth century.

The advent of the Industrial Revolution around 1780 had important consequences for chandelier design. Mechanisation and technological advancements reduced manufacturing costs and facilitated higher standards of craftsmanship. An example of this is the invention of a machine that could cut crystals with perfect precision by Daniel Swarovski in Austria, which he patented in 1892. In addition, industrialisation meant that wealth became more widely distributed across society, with a growing middle class being able to afford luxury goods such as chandeliers for their homes. As in France under Louis-Philippe and Napoleon III, the trend in nineteenth century England was towards reviving older styles, especially from the Georgian, Baroque and Rococo periods. Increasing numbers of people aspired, and were able to afford, to emulate the lives of the old aristocrats through acquiring luxurious ornamentations.

The nineteenth century was also a time when new sources of light emerged and gradually came to eclipse the use of candles. These were generally cheaper, much brighter, more efficient and required relatively little maintenance. Early in the century, oil- and then kerosene-burning chandeliers made an appearance (Mccaffety, 2006). By the 1840s, gas lighting was common and the gasolier emerged in the second half of the century. These were often made in the intricate Rococo style and featured both gas burners and candle arms. As gas flames were found to burn too brightly in comparison to candlelight, opaque shields made of alabaster were often added to soften the glare. However, it was the invention of the electric light bulb in 1879 by Thomas Edison that had the most transformative effect on chandelier and lighting design more generally. Lightbulbs very quickly became widely available in lighting fixtures for domestic use. Chandelier designs were adapted in several ways. Most notably, solid glass stems and arms were replaced with hollow versions so that they could accommodate electric wiring. Many of F&C Osler’s chandeliers were manufactured in this way from the late 1800s onwards. The absence of candles also meant that chandelier arms and lighting fixtures could be twisted downwards with light being directed down into the room.

It is helpful to explore the evolution of the Venetian chandelier in separation from the other Europe styles already discussed. This is because its development followed a quite separate trajectory, resulting in distinct styles and techniques of manufacture. Venetian chandeliers are the product of the exceptional glass-making industry of Murano, a small island near Venice. The history of Murano glass began in 1291 when it was ordered that all glass manufacture should be transferred from Venice to the island due to the risk of fire. Shortly after, the Venetian Republic introduced strict laws banning emigration and local glassmakers from practicing their craft outside Murano. These measures represented an attempt to contain glass production and its coveted secrets in one place and thereby retain a competitive advantage in the face of foreign competition. However, despite the enforcement of increasingly harsh punishments for defiant glassmakers, which included imprisonment and killings, emigration from Murano to the rest of Europe was to continue throughout the coming centuries (Magno, 2011).

The golden age of Murano glass production roughly spans the fifteenth to the early seventeenth centuries. The industry took off in the 1400s after Angelo Barovier invented the perfectly transparent glass known as crystallo which was to become exceedingly popular across Europe. Unlike rock crystal or lead glass, Venetian glass is not cut. Instead, it is melted and moulded which makes it more malleable, lending itself to intricate designs and also a softer appearance. Barovier, along with his descendants, developed many of the techniques which lend Murano glass its distinctive style, including chalcedony used to create multi-coloured glass (millefiori) and milk glass (lattimo) which was inspired by Chinese porcelain.

However, it wasn’t until the 1700s that the first glass chandeliers appeared. A particularly renowned craftsman during this period was Giuseppe Briati (1686-1772). He specialised in the production of what is now recognised as the classic Murano chandelier. These comprised a central metal axis from which emanated numerous arms decorated with polychromatic or transparent flowers, leaves and fruits, as well as moulded crystals. This new style of chandelier was known as a ciocche, meaning bouquet of flowers. Their ornateness, exoticism and colour reflected the Baroque and Rococo influences of the time. Briati is also famed for creating the Rezzonico chandelier, named after the palace that now houses the Museum of Eighteenth Century Venetian Art. As the image below illustrates, these chandeliers were often very large as well as being amongst the most colourful and intricate of all styles (Mariacher).

Unfortunately, it was precisely the popularity of Murano glass that would lead to a period of crisis characterised by a substantial decline in demand and production from the late seventeenth century on. Despite protectionist measures, Venetian-style glass was being imitated across Europe. France under Louis XIV was particularly keen to free itself from importing Venetian products, and employed tactics to encourage Murano’s glassmakers to immigrate to Paris. It was relatively successful in this endeavour which resulted in the founding of the Saint Gobain company in 1665, which became a leader in crystal production.

Glass production in foreign markets also began to pose a serious challenge around this time. In particular, Bohemian glass made of potash crystal and ideal for engraving was becoming increasingly popular, as was English lead glass with its high refractive properties. Foreign competition became ever more intense throughout the eighteenth century until crisis struck when Napoleon’s troops invaded in 1797 and the Venetian Republic ceased to exist. Along with many other industries, glass production declined dramatically, many furnaces closed down and some techniques were entirely forgotten.

The tide of decline began to be reversed from the 1840s on. This was in large part due to the work of celebrated Murano-born glass historian Vincenzo Zanetti (1824-1883) who made it his mission to revive the island’s foundries and traditional production techniques. In 1861, he established the Museum of Glass on Murano in order to gather the best examples of glassware as a source of inspiration for future generations. He also opened a school, which is still in operation today, for experienced glassmakers to train young apprentices. In 1864, the first exhibition of Murano glassware was held on the island. Murano glass was also showcased and highly praised at the universal exposition in Paris in 1867. The unification of Italy during this period also created a more favourable climate for Italian-made products, including Murano glass, to compete with other European countries. All of these developments contributed to the revival of Murano glass and spurred its growing popularity. Pietro Bigaglia, Angelo Ongaro, Giovanni Fuga, Vincenzo Moretti and Andrea Rioda are all examples of craftsman who studied and revived ancient techniques such as murrine and milk glass (Mariacher). To this day, there is a high demand for Murano glass chandeliers which continue to be exported all over the world.

It is important to emphasise that throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the great historic European chandelier styles have remained remarkably resilient. The Dutch brass-ball stem, French Baroque and Georgian chandeliers, especially, have clearly stood the test of time. Still today, traditional chandeliers not only survive, but are thriving, being continually emulated and reworked. There has never been a wider range from which to choose, whether they be reclaimed period pieces, relatively inexpensive repro models or handmade in traditional styles (Wilhide, 2005).

The chandelier did fall out of favour in design circles around the late twentieth century, owing to the fact it was considered to be at odds with the preference for modern minimalist interiors (Wilhide, 2005). Yet over the past couple of decades there has been a strong revival of interest amongst designers and the general public. In today’s modern homes, traditional chandeliers are increasingly placed in simple contemporary settings to create a striking juxtaposition between old and new.

Having said this, there were some important design trends that made a resolute break from traditional styles. The Art Deco movement of the 1920s and ‘30s saw designers enthusiastically embrace the materials and structures of modern technology. The Paris Exhibition of 1925 featured some impressive chandeliers made in the Art Deco style. The Art Noveau style of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (circa 1880-1910) also involved a rejection of traditional styles. Artists and designers turned instead to nature for inspiration, and chandeliers typically incorporated designs featuring sinuous lines, vines, flowers and insects. Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933) was perhaps the most prominent figure of the Art Nouveau movement and is particularly famed for his electrolier designs made with stained glass.

As previously mentioned, chandeliers fell out of favour for a considerable period during the latter part of the twentieth century when minimalism and hidden or recessed lighting was the norm. In recent decades, though, modern designers have enthusiastically embraced the chandelier and are creating innovative designs entirely unrelated to previous styles (Wilhide, 2005). The wide range of unconventional materials now being used, combined with innovations in lighting technology, such as LEDs and fibre optics, has served to broaden the concept of the chandelier considerably, as the examples below attest.

Swarovski launched the “Crystal Palace” collection in 2002 which featured several innovative reinventions of the chandelier, including Tord Boontje’s “Blossom” design consisting of an asymmetric floral branch adorned with LED lights. Ron Arad’s “Lolita”, also made for Swarovski, features an interactive spiral-shaped pixel board designed to display text messages via SMS and which comprises over two thousand crystals set with LEDs. Today’s chandeliers are being made with increasingly unusual materials, often to produce a witty or ironic effect. One example is “I Spy” by Habitat, a chandelier made of multiple tiers of plastic magnifying glasses which fracture light in a similar way to crystal. In 2002, Peter Valois and Michael Marra of Touch Design created a chandelier using over 20 martini glasses. Others have made chandeliers out of wine glasses, broken plates, glass bottles, discarded bike parts and even gummy bears. Finally, the British designer Sharon Marston has pioneered the use of fibre optic technology in chandelier design. She has created many notable one-off pieces using woven nylon and fibre optic filaments and featuring petal, feather or shell forms to create a striking ethereal effect. Her collection entitled “Brilliant” was the first ever contemporary lighting piece to be exhibited at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

We have so many beautiful chandeliers on our site that it might be a bit daunting if you are just starting your search for the perfect chandelier. There are so many search terms to try. Let’s start at your front door,for example. You can look for hallway and foyer chandeliers, or for stairwell and staircase chandeliers. Large chandeliers look good in stairwells too. On top of that, you might have a style in mind. You may be looking for antique chandeliers or vintage chandeliers, or modern designer chandeliers for your home, or spectacular Swarovski crystal chandeliers. The choice is seemingly endless! So where do you start? Anyone visiting our site will usually be looking for luxury chandeliers or luxurious chandeliers, and they appreciate good quality and design. Our team have over 4 decades of combined experience of talking to customers who need help.We know our stuff. We know the products. On top of that, we usually know the glassmakers and the owners of the studios who are responsible for creating these beautiful products. So put yourself in our hands. Read our blogs. Give us a call, and tell us what you want. We are here to help you.